Categorized: History Freemasonry

Tagged: European Freemasonry Regius Manuscript stonecutters

I have recently started to read 19th and 18th-century books about Freemasonry as an ongoing study in the history and origin of Freemasonry.

I have always been interested in the transition from the Guilds of Master Builders to Speculative Freemasonry and to find answers to the following questions.

What is the significance of the similarity of rituals and symbols used by ancient secret societies in relation to Freemasonry?

Regarding the construction of their temples, why are they leading from West to East and why is the cornerstone placed in the North East as they are in our Lodges. The fact that both Solstice celebrations and the art of Geometry play a big role in secret societies from the Magi to the Egyptians, the ancient Greeks, the Romans even the Druids in Great Britain and Europe is yet again a subject I hope to explore.

Early 19th century a sincere desire to investigate the origin, history and principles of Masonry began to be manifested among German Masons, and the first attempt was then made to compile, select, and submit to critical examination the scattered opinions of Masonic authors.

The only complete and connected history was contained in the manuscript work of J. A. Fessler , “Versuch einer critischen Geschichte der Freimaurerei und der Freimaurer – Bruderschaft von den ältesten Zeiten bis auf das Jahr 1812”. – Translation: An attempt at a critical history of Freemasonry and the Freemason Brotherhood from the earliest times to 1812.

This manuscript makes the intimate connection between, Freemasonry and the Operative Masons of the Middle Ages and trace back its history to the Roman Architectural Colleges, who like Operative and Speculative Masons organised themselves in Lodges. Marcus Vitruvius Pollio, commonly known as Vitruvius, was a Roman author, architect, civil and military engineer during the 1st century BC, known for his multi-volume work entitled De Architectura.

According to Vitruvius, the Members were required to be well skilled and to have a liberal education.

Three Members were, at least, required to form a College, and no one was allowed to be a Member of several Colleges at the same time. The Members, after hearing the reports of their Officers and deliberating thereon, carried their resolutions by a majority of votes; and in the same manner, Members were enrolled and Officers elected.

The custom which prevailed among the Operatives we find that besides the legitimate Members of the Corporation, lay or amateur Members (often patrons) were admitted. The Corporations held their meetings in secluded rooms or buildings exclusively appropriated to that purpose, and most of them had their own schools for the instruction of Apprentices and lower grades of workmen. The Members took an oath to assist each other; poor Members received relief, and on their demise were buried at the expense of the Corporation.

They also kept registers of the Members (similar to the lists or directories of today’s Lodges). The Masters, Wardens, Fellowcrafts and Apprentices, Censors, Treasurers, Keepers of Archives, Secretaries / Scribes, and Serving Brethren; their tools and working implements carried a symbolical meaning; and it is worth noting that in religious matters they were tolerant.

Taking the manuscript of J. A. Fessler into consideration, and combining with manuscripts of the 17th century, it is safe to state that the modern Freemason Society is the direct descendant and successor, in an unbroken line, of the Operative Fraternity of Masons of the Middle Ages which found their roots in the Roman Architectural Colleges.

It was only when the Fraternity of “Steinmetzen” (Stonecutters) had attained to perfection, or rather was on the decline, that the real history of European Freemasonry according to its existing signification commences.

With the spread of Christianity throughout Germany and the requirement for Roman bishops to raise cathedrals, the Masonic colleges in Germany thrived. Generally designated as Steinmetzen or stonecutters, these Masonic fraternities raised churches and cathedrals throughout continental Europe.

The society of stonecutters had within it a variety of grades and occupations. These included Steinmaurer or stone layers, Steinhauer or stone hewers, as well as Steinmetzen, a word derived from Stein (stone) and Metzen, a derivative of the word Metzel or chisellers, a more detailed and skilful art than the hewers. The construction of Bauhütten or lodges situated next to the churches being constructed served as design, work and sleeping quarters.

One of the earliest records of Masonic lodges is found in the German city of Hirschau (now Hirsau) in the current state of Baden-Württenberg. Masonic lodges instituted in the city of Hirschau in the late 11th century worked under the Benedictine order of Germany and were the first to establish the Gothic style of architecture.

As early as 1149 the first German Zünfte or stonemason unions developed in Magdeburg, Würzburg, Speyer and Straβburg. In 1250 the first grand lodge of Freemasons was formed in the city of Cologne Germany. The grand lodge was formed as part of the immense undertaking to erect the cathedral of Cologne.

The first Masonic Congress occurred in the city of Straβburg, Germany in the

year 1275. It was formed by Grand Master Erwin von Steinbach. This was also the earliest recorded use of the symbol of Freemasons, the square and compasses.

Whilst Straβburg was considered the premier grand lodge of the day, other

Great Masonic lodges had already been formed in Wien, Bern and the above

mentioned Köln (Cologne); these were called Oberhütten or great lodges.

Several Masonic congresses were held in the city of Straβburg, including

the years 1498 and 1563. At this time the first recorded Arms of the Masons of Germany were recorded depicting four compasses positioned around a pagan sun symbol and arranged in the shape of a pagan sun-wheel. The Masonic Arms of Germany also displayed the name of St John the Evangelist, the patron Saint of German Masons.

The Oberhütte of Cologne, and its grandmaster, was considered the head of the Masonic lodges of all upper Germany. The grandmaster of Straβburg, in those days a German city, was head of Masonic lodges throughout lower Germany, Franconia, Bavaria, Hesse and the main areas of France.

The grand lodges of Masons in Germany received support from the Church and the Monarchy. Emperor Maximilian reviewed the Masonic congress of 1275 at Straβburg and proclaimed his protection over the craft. Between 1276 and 1281 Rudolf I of Habsburg, a German king, became a member of the Bauhütte or Lodge of St Stephan.

King Rudolf was one of the first non-operative, otherwise called free or speculative members of a Masonic lodge.

The statutes of Masons in Europe were revised in 1459. The revisions described the requirement to test foreign brothers prior to their acceptance in lodges via an established (seemingly international or European) method of greeting.

The first grand assembly of Operative Masons in Europe occurred in the year 1535, in the city of Cologne in Germany. The bishop of Cologne, Hermann V, assembled 19 Masonic lodges to establish the Charter of Cologne written in Latin.

In 1563 the Ordinances and Articles of the Fraternity of Stonemasons were renewed at Chief Lodge at Straβburg on St Michael’s Day. These regulations demonstrate three important links to modern Masonry.

Firstly, apprentices were termed ‘free’ on completion of service to their Master, which likely is the origin of the word ‘Freemason’.

Secondly, the fraternal nature of the lodge was depicted in a range of regulations such as services to the sick, or the practice of teaching a brother without cost.

Thirdly, the Freemasons used a secret handshake as means of identification.

Two articles from the regulations indicating these points are:

1) “No Master shall teach a Fellow anything for Money. And no craftsman or master shall take money from a fellow for showing or teaching him anything touching masonry. In like manner, no warden or fellow shall show or instruct anyone for money in carving as aforesaid. Should, however, one wish to instruct or teach another, he may well do it, one piece for the other, or for fellowship sake, or to serve their master thereby.

2) Every apprentice when he has served his time and is declared free, shall promise the craft, on his truth and honour, in lieu of oath, under pain of losing his right to practise masonry, that he will disclose or communicate the mason’s greeting and grip to no one, except to him to whom he may justly communicate it; and also that he will write nothing thereof.

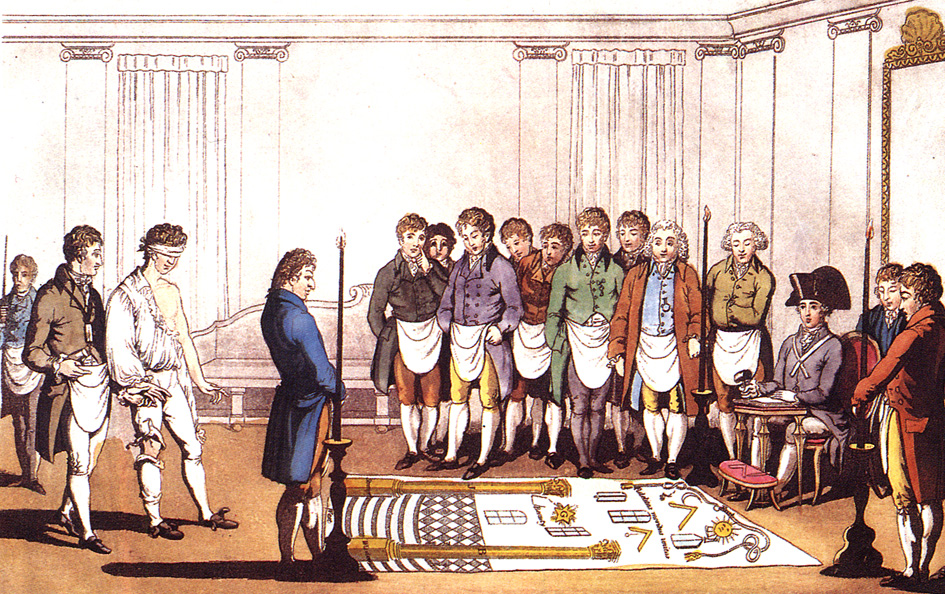

The Straβburg ordinances stipulated that entry into the fraternity was by free will and clearly indicated the three grades of Entered Apprentice, Fellow or Companion and Master. They required the taking of an oath and for masons to meet in chapters called ‘Kappitel’. The ordinances clearly instruct masons not to teach Masonry to non-masons.

That German Masonic lodges and grand lodges existed prior to the formation of the grand lodge of England in 1717 is clear. As is their use of

secret handshakes, the use of the term ‘free’ and their acceptance of non-operatives. The use of allegory and layered symbolism, which makes the

Masonic fraternal system unique, was also evident in German lodges of the time as displayed in the stone carvings and architectural styles of the churches and abbeys they built.

The source of the remaining text is from the book “99 Degrees of Freemasonry” by Henning Andreas Klovekorn. (October 2, 2015)

“99° of Freemasonry” supports the theory that the seed of modern Freemasonry, was not linked to Knights Templar or English Freemasonry, but originated with the Masonic Institutions of Germany, who in turn, had received their Masonic knowledge from earlier Masonic organisations.

This claim is supported by the following 7 points.

- The Regius Manuscript (late 14th century), the Oldest (reputable) surviving Masonic text in Britain, makes reference to the four crowned martyrs, which are unequivocally linked to the legend of Masons under the Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation, a Masonic tradition originating in Germany, not Britain.

- The existence and earliest recorded use of the square and compasses (the fraternal sign of Freemasonry) on the arms of German Masonic Bodies.

- The existence of highly organised Masonic institutions (Steinmetzen) in Germany in the 13th century, such as the Grand Lodge (Oberhütte) of Straßburg and Köln (Cologne), and several subordinate Masonic lodges, which not only worked in stone but also included allegorical Masonic teachings within their guilds.

- The election of a Grand Master of Masons in the 13th century and the establishment of grades of apprentices, fellows and master masons in Germany in the 12th century possibly earlier.

- The establishment of printed Statues and Rules of the Masonic Order in Germany before the establishment of written Masonic statues in Britain.

- The inclusion of non-operative (or speculative) members, such as King Rudolf I into Masonic Lodges in Germany in the 13th century.

- The first large-scale recorded requirement for Masonic lodges to utilise a secret method of greeting and ‘grip’.

“99° of Freemasonry” also analyses the use of the square and compasses, as allegorical moral symbols of masonry, in works of art within German culture of this period, further evidence of Masonic philosophy within German culture and continental Europe in this period.

Whilst many Freemasons have been ‘conditioned’ to accept that the origins of Masonry stem from England, as modern-day Masonic Regular Grand Lodges are deeply interconnected with, and influenced by the United Grand Lodge of England “99° of Freemasonry” sheds new light on Masonic history and urges if not inspires Freemasons to look to the continent of Europe as the first seed of Masonry.